KOZANI

Portfolio

KOZANI

KOZANI, Greece (AP) — At Greece’s largest coal mine, controlled explosions and the roar of giant excavators scooping up blasted rock have once again become routine. Coal production has been ramped up at the site near the northern Greek city of Kozani as the war in Ukraine forced many European nations to rethink their energy supplies.

Coal, long treated as a legacy fuel in Europe, is now helping the continent safeguard its power supply and cope with the dramatic rise in natural gas prices caused by the war.

Electricity generated by coal in the European Union jumped by 19% in the fourth quarter of 2021 from a year earlier, according to the EU’s energy directorate, faster than any other source of power, as tension spiked between Russia and Ukraine and ahead of the invasion in late February.

Russian gas made up more than 40% of the total gas consumption in the EU last year, leaving the bloc scrambling for alternatives as prices rose and the supply was cut off to several nations. Russia also provided 27% of the EU’s oil imports and 46% of its coal imports.

The crisis caught Greece at a difficult moment in its own transition.

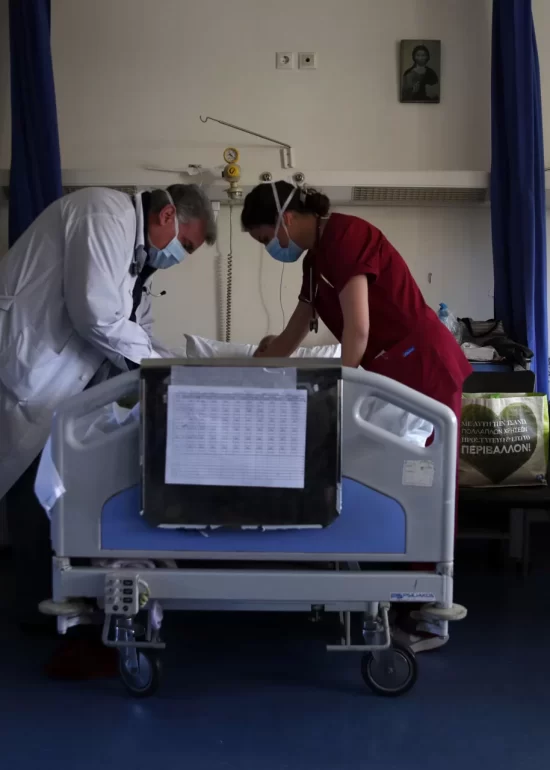

For decades, the country relied on the domestic mining of lignite, a low-quality and high-emission type of coal, but recently accelerated plans to close down older power plants, promising to make renewables the main source of Greece’s energy by 2030. Currently, renewables account for about a third of the country’s energy mix.

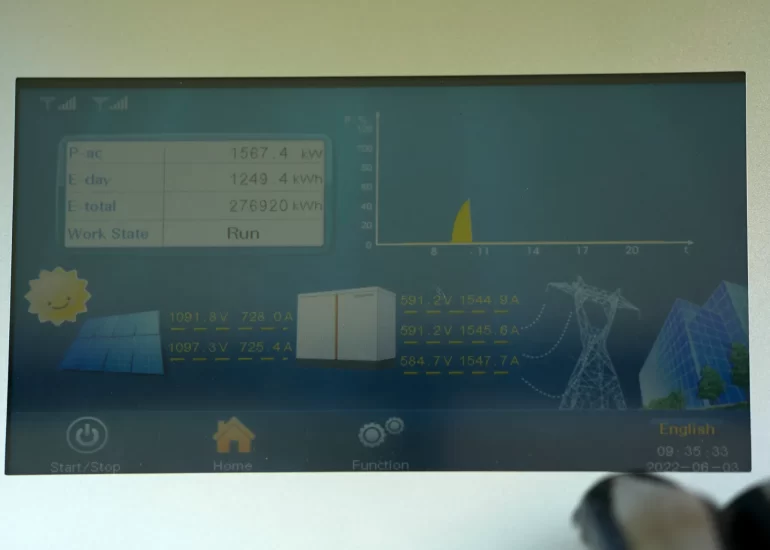

A newly-completed solar park, one of Europe’s largest, is just a half-hour drive from the country’s biggest open-face lignite mine, near the northern city of Kozani.

While inaugurating the new solar facility, Greece’s prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, announced a 50% hike in lignite production through 2024 to build up reserves. Plans to retire more coal-fired power stations were paused.

“Not only Greece but all European countries are making minor amendments to their energy transition programs with short-term ‒ and I stress short-term ‒ measures,” Mitsotakis said at the April 6 event.

Officials in Greece say the country is naturally suited to developing solar and wind energy. It’s testing EU-sponsored battery technology to try and wean its islands off costly and polluting diesel-power local electricity plants.

The Kozani mine covers an area nearly nine times the size of JFK Airport in New York: A black basin sunk into land surrounded by forests and poppy fields. Excavators use clawed wheels taller than the side of a house to load coal into long lanes of belt conveyers.

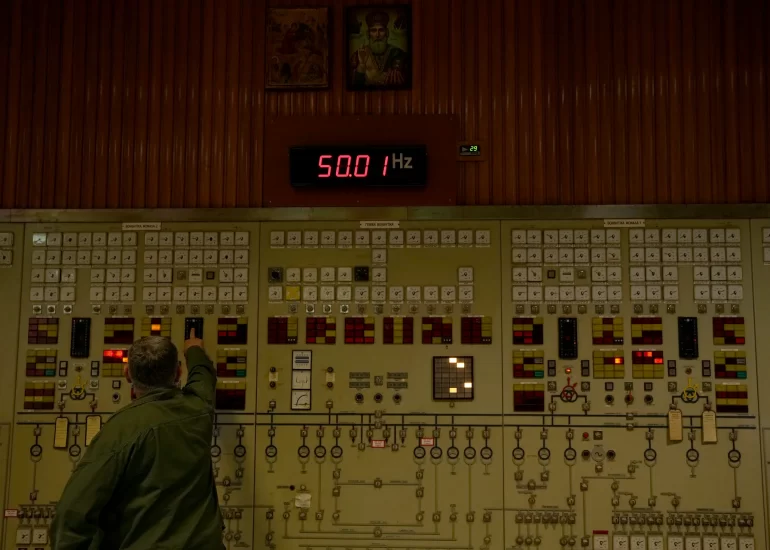

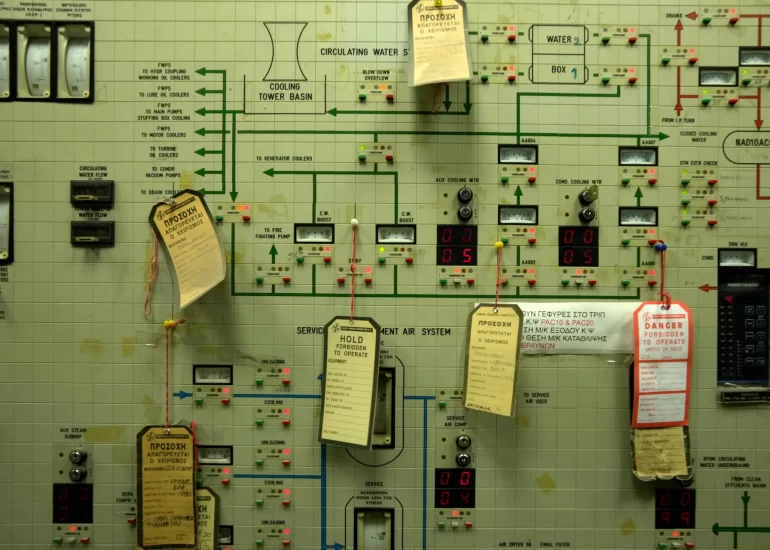

“This was the heart of Greece’s energy production,” mine director Antonis Nikou said, speaking at the plant and standing near the Orthodox Christian church of Saint Barbara, the traditional protector of miners, firefighters and others who face danger at work.

Nikou views the end of Greece’s coal era as inevitable, a belief shared for the rest of the EU by its own policymakers and many experts who argue that coal’s brief return will serve only as a backstop while countries ramp up renewables and update their power grids.

“Attempting to feel secure in terms of not getting cold next winter, that’s understandable but this is a very short-term arrangement,” said Elif Gunduzyeli, a senior energy policy coordinator at Climate Action Network Europe, a Brussels-based coalition of environmental campaigning groups.

Money needed to modernize the coal industry and find new deposits, she argues, is no longer attracting investors.

Western Europe’s postwar integration was largely driven by coal ‒ the European Coal and Steel Community formed in 1951 eventually evolved into the European Union ‒ but EU consumption has long been eclipsed by other nations. China uses more coal than the rest of the world combined.

EU coal consumption plummeted by more than 60% in the last 30 years, the drop accelerating since 2018.

Regulation in Europe and how it reaches international climate goals are closely watched by other industrial powers, along with how it manages to rescue local economies in vanishing coal-mining communities.

Officially named the West Macedonia Lignite Center, the mine at Kozani now employs 1,500 workers, down from as many as 6,000 in 1990s. The 400-hectare (1,000-acre) solar park nearby hires just 20.

Greece’s power workers’ union is pressing the government to give coal a longer lease of life, instead of using gas imports that are now more expensive.

“It is clear that this transition did not take place on fair terms but in a way that supported the interests of natural gas,” union leader George Adamidis told the AP in an interview. “We have made a decision to move away from Russian natural gas, but the import of liquified natural gas from the United States and elsewhere also involves a process that is polluting so it doesn’t serve our climate goals.”

The union wants to extend the life of modern coal-fired plants by about five years, through 2035, and even increase its share of electricity generation from currently less than 15% to about 25%.

The government says money from the European Union’s Just Transition Fund, set up to help coalmining communities and others hurt by the transition, will be used to help regions like Kozani with multiple schemes including the restoration of mined land.

But Pavlos Deligiannis, a retired mine worker, urged authorities to extend the transition and give alternative industries tax breaks and other financial incentives to invest in the region and create jobs.

“We all know that coal has an expiry date,” he said. “Our young people are leaving the city… If you want a smooth transition, you think about the next business before you close the existing one. That’s not what happened here ‒ we did the opposite and we are not prepared for the green transition.”