GREECE RAISING SHIPWRECKS

Portfolio

GREECE RAISING SHIPWRECKS

Nagorno-Karabakh’s 150,000 people don’t hold Azerbaijan passports and can travel only to Armenia, unless they a

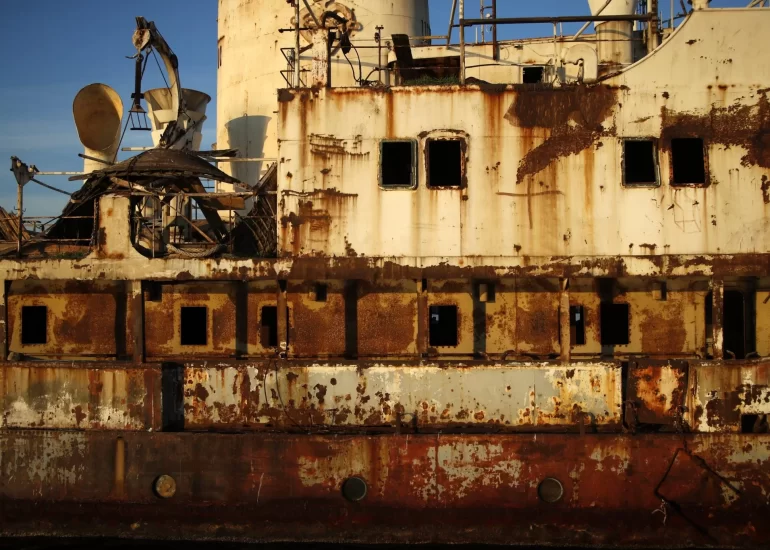

The hulking remains of a cargo ship rise up through the water, listing to one side with a rusting hull exposed, its glory days of sailing the world’s seas and oceans long gone.

This is just one of dozens of abandoned cargo and passenger ships that lie semi-submerged or completely sunken in and near the Gulf of Elefsina, an industrial area of shipyards and factories near Greece’s major port of Piraeus.

Now Greek authorities have begun to remove the ships, some of which have been there for decades, saying they are both an environmental hazard and a danger to modern shipping.

“We are speaking about 27 shipwrecks and potentially … 12 harmful and dangerous ships,” said Charalampos Gargaretas, the chief executive officer of Elefsina Port Authority. ”(It’s) a tragic situation.”

From the port of Piraeus to the island of Salamina that lies off of Elefsina, the sea is littered with 52 such shipwrecks, said Dimosthenis Bakopoulos, head of Greece’s Public Ports Authority.

“You don’t have to be a scientist to understand that the shipwrecks are an environmental bomb that degrades the environment of the nearby municipalities,” Bakopoulos said, adding that some of the ships were still leaking petroleum products into the sea.

But the process has been wrought with difficulties.

The owners of the ships vary from individuals to inheritors to companies registered in countries ranging from Greece to the Marshall Islands, Britain and Honduras. Some have gone bankrupt, some are no longer traceable, officials say. So authorities have put in motion a process where the abandoned ships can be appropriated by the state.

Salvage companies then take over the job of breaking up the ships and removing the remains — a job they undertake free of charge to the state in return for being able to sell the metal for scrap.

Another problem Greek authorities have faced is the lack of licensed ship-breaking yards in the area, and some opposition from locals who fear the environmental impact of large ships being demolished in their area.

“It is the sins of many years which we now have come (to solve),” said Gargaretas. “We are trying in a very short period of time and with huge bureaucratic and legal hurdles to remove all these ships from the area.”

pply for Armenian passports. The mountainous region’s self-declared sovereignty isn’t recognized by any country. With trade, travel and educational opportunities limited, the region’s youth are in danger of falling behind.

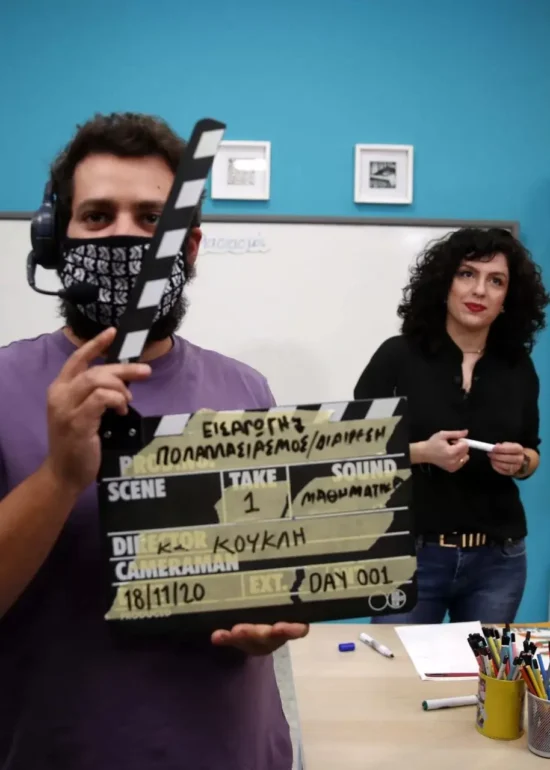

The privately funded TUMO Center for Creative Technologies, which teaches subjects such as robotics and 3-D modeling, epitomizes the aspirations in the region to emerge from the isolation that has cloaked it for more than two decades. Nagorno-Karabakh has been under the control of ethnic Armenian forces backed by Armenia since the end of a 1994 war.

Nagorno-Karabakh has reported solid gross domestic product growth over the past decade. Once heavily reliant on imported electricity, Nagorno-Karabakh now has a self-sufficient grid.

It also has an international airport, built in 2011, but the one thing missing are the planes. Azerbaijan has warned it can’t guarantee the safety of flights to Nagorno-Karabakh. So, neatly stacked luggage trolleys, check-in desks and an air traffic control tower remain unused.